How do you take and eDNA sample?

A little more on the eDNA sampling from the last post. The photos here show the filter after each syringe of water has been passed through. You can see the colour change after each syringe, the last one being quite striated and dark. As DNA is in the water, the aim is to pass as much water through the filter as you can- more water means more DNA collected to test and the greater the chance of detecting your target species (or a greater range of species if you do a broad test). 👩🔬

You stop filtering water through the filter when the pressure becomes too great and it is no longer possible to.

What does it tell us?

The samples of DNA that we collected last about 5 days in the environment before they are too damaged to be used in testing. This means that if you get a positive results, the species has been their very recently. It can therefore be a great complement* to other types of evidence that a species is in an area, such as scats (poo), hair, scratches, rub marks, nest, egg shells, bones etc., depending on the species in question and the purpose of the research.

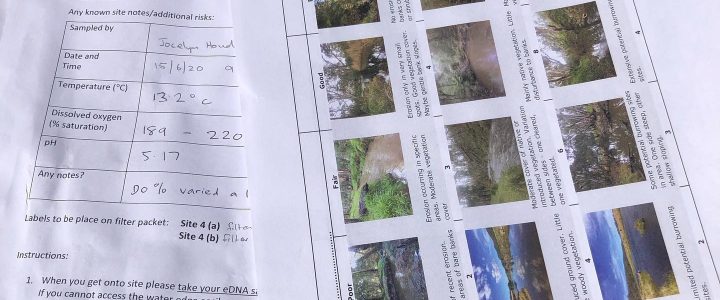

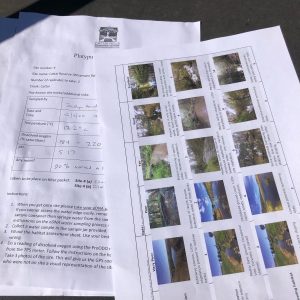

You can also see me doing a habitat assessment to determine how much suitable platypus habitat there is at each site. We also tested water temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH and other water quality indicators. 🔬 Oh and no, the eski is not for beers (although the location is beautiful), the samples go in an eski to stay cold and help with preservation.

What we get overall is picture of:

- If there are platypus there

- What sites are suitable based on habitat and water quality and

- If the habitat was suitable but the water quality wasn’t, we know what might be affecting them and can investigate to improve the water quality and a few other things.

All these things help inform future research, protection of area and our understanding platypi.

Watch this space for results!

Photos: Students from WSU sampling the creek, Habitat Assessment sheets, (far above) eDNA filters from start to finish of the filtering process.